Over the next several months I will focus the Amazing Grazing column on the topic of implementing a Regenerative Grazing system in the Southeastern US, based on examples from my own production system. I have been farming in Southern Virginia and Northern North Carolina near the little border town of Virgilina, VA for most of my life, and I consider myself to be a regenerative farmer.

When I was a child, my parents bought a small tobacco farm, “Pleasant Hills Farm” which is located 6 miles southwest of Virgilina. My family, including all 7 kids, traveled to Pleasant Hills every summer during my childhood for 1 to 3 months to work in the tobacco and to experience the life of farm kids. This gave us insight into my father’s upbringing on a small farm in Virginia. Dad wanted us to experience the hard work and rich rewards of a life in agriculture. Not all of us fell in love with the lifestyle, but as soon as I was allowed to run a tractor and bush hog (at age 8!) I fell in love with it and thereafter identified as a farmer.

When I was in my first year in college, my folks bought a larger farm, Triple Creek Ranch, located one mile east of Virgilina. Triple Creek has a lot more pasture than Pleasant Hills, and between the two farms we ran about 100 brood cows. After college and meeting my spouse Jeannette Moore, we moved to Pleasant Hills to operate the farm. This was hard work and unfortunately in 1982 the future of agriculture and farmers looked pretty bleak, so we returned to graduate school to get more education and potentially more secure careers. This broke my heart at the time as I still thought of myself as a farmer, but I had to face reality and make sure we could make ends meet as the years went by.

When I came to the end of my graduate student days I landed the job I still hold at NC State, which allowed me frequent opportunities to be on the farm. I also realized I had the perfect situation to try new practices myself before recommending them to my clients. Examples include developing mineral formulas and new mineral feeder designs, use of supplemental feeds like soybean hulls and whole cottonseed, novel endophyte tall fescue and other alternative forages, temporary fencing, alternative hay feeding programs and grazing strategies. All of these practices were tested out on my own cows before I ever recommended them broadly. Along the way there were things we tried that didn’t work; most of those you never heard about.

Despite my active career at NC State as an Extension Beef Cattle Specialist, I still continued to identify first as a farmer. I often told folks this, and that NCSU was my second “public job” which is something farmers in my area often had to seek out to make ends meet.

One thing that has been with me my whole life, but that just came into focus in recent years, is the understanding that our land is clearly not what it once was. Before the civil war there was very little agriculture in our area and the early settlers could clear the land, till it, and grow some amazing crops. This is because the top soil had been enriched by natural processes over the millennia which gave it a high organic matter content and the inherent ability to produce. Unfortunately most of the land was highly erodible, so much of that rich topsoil soon washed away.

Starting in the late 1800s the tobacco industry in our area started to expand, and much of the land was converted to this cash crop. As it turned out tobacco is a plant that thrives in poor quality soil so it did quite well even as extensive tillage continued to destroy the health of the soil. Production was on raised beds that allowed the soil to drain in wet weather, and this obviously resulted in a lot of erosion.

Around the turn of the century a new problem developed in our area. A bacterial wilt disease, named Granville Wilt, wiped out the tobacco crop and this problem persisted to the point that tobacco farming was no longer a viable way to make a living on many farms. No other crop could thrive in the degraded soils. Much of the population that had sufficient resources left our region, called the Old Tobacco Belt, and settled in the area around Raleigh, NC which came to be known as the Middle Belt. Residents also moved to the eastern counties of NC eventually known as the Eastern Belt and the region along the South Carolina border known as the Border belt. Life in the Old Belt changed dramatically, and much of the land that was cleared grew up in forest. Eventually wilt resistant varieties of tobacco were developed, and this helped bring back some tobacco production, but it never returned to the glory days of the early 1900s.

When I was a child I remember walking in the woods and seeing trees coming right up out of raised beds. When I asked the farmer that raised our tobacco about this he told me the story about why most of the land had been allowed to “grow up”. I also have childhood memories of the deep gullies that were on Pleasant Hills when we bought it. There were a lot of cedars and other trees growing up on the pastures that needed to be cut, and an old barn that needed to be torn down, so we put all this debris in the gullies to try to hold the land.

With help from the Soil Conservation Service we also fixed the gullies and planted grass waterways on all the cropland to try to reduce the erosion. We also started using Italian Ryegrass as a winter cover crop, but the heavy tillage needed for tobacco production continued. As kids we did a lot of work in the tobacco learning how to hoe weeds and wiregrass, pull suckers, top and prime. I have a clear memory of being caught in a rain storm priming ground leaves and having balls of soil built up on my boots to the point I could not walk. I didn’t realize at the time that this was because of the complete lack of organic matter in the soil.

When I returned to the farms from graduate school I came to realize that we had a long way to go to get to a place where we could be successful. Soil testing revealed that much of the pastureland was very low in pH (5.0) and we had very low phosphorus status. The predominant grass on the better parts of the farm was tall fescue which had been planted in the 60s, but the less productive land was mostly broomstraw and blackberries.

After a lot of lime and fertilizer on the marginal areas they started producing a lot better. However, it was clear how important fertilizer was as we would fertilize with nitrogen, and then about 6 to 8 weeks later you could literally see when the nitrogen ran out as the dark green grass would suddenly turn yellow except where there happened to be a cow pie or urine spot. We regularly added fertilizer both spring and fall and the grass grew pretty well which gave us enough grass to graze for about 8 months, with about 4 months of hay feeding.

We also occasionally used herbicides in the system to kill certain weeds that were problems like buttercups. Unfortunately at that time the herbicides were not that good for problem weeds like horsenettle, dog fennel and blackberries. We mowed about twice a year to keep these problem weeds in check.

In my work at NCSU I started to get involved in the Amazing Grazing Program where I was exposed to the concepts of plant growth, soil management, and grazing management. About 2008 I met Ray Archuleta who worked with NRCS at the time as one of their first Soil Health Specialists. Ray has a very different way of looking a things, and he convinced me that I still had a long way to go in developing the kind of production system I needed.

I also met Dr. Alan Franzluebbers who is a soil ecologist with USDA-Ag Research Service. Alan has worked his whole career developing ways to predict nutrient cycling in soils, and to help farmers be more efficient with their fertility programs. From Alan I learned that healthy soils store high levels of plant nutrients (like nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium), which are released when soil microorganisms break down organic matter.

About 15 years ago the term “Regenerative Agriculture” was coined to describe systems that would continuously improve the functioning of the ecosystem to help reduce the needs for external inputs. First applied to cropping systems it was quickly expanded to grazing systems, and folks started talking about Regenerative Grazing Management.

One day I came to the realization that while we had done a lot to improve things, we still had a long way to go to make this land as productive as it once was before all the top soil eroded away. We are faced with the great challenge of rebuilding from what remains of the original soil, essentially the “B Horizon”.

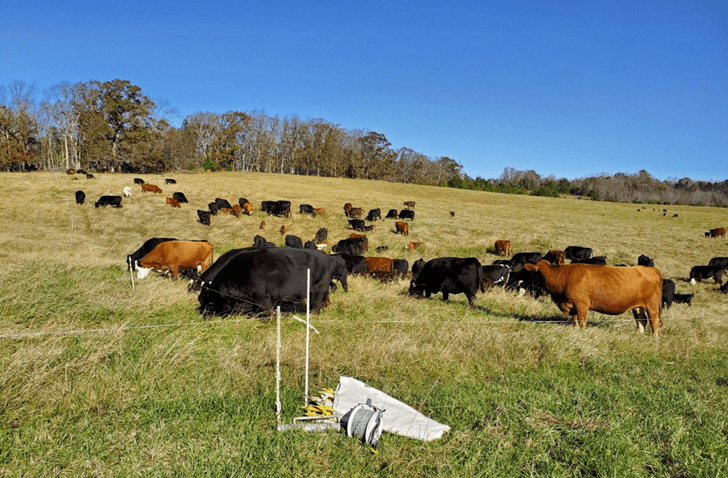

We began to graze in a much different way, with frequent animal movement, high stock density (lbs of livestock per acre on a given day), and increased residual plant material. We unrolled hay on the areas where we obviously needed nutrients. This was similar to how we had managed before, but now it was with the express purpose of improving organic matter and soil function. The stomped forage or hay was no longer “wasted” but was intentionally left to feed the soil biology.

Under our management the productivity of our soils has slowly improved. We now use fertilizer only strategically when we know it will really give us an economical response. We no longer see the nitrogen run out like we used to in the old days.

While there are much more effective herbicides now, we use them very sparingly only to address really bad weed problems or in other specific cases where they make sense. In general, we have managed with much longer rest periods to increase plant diversity. Because most plants are allowed to go to seed, we have a lot more clover, but also many other “forbs” which we once called weeds. We also have many other grass species that grow in combination with tall fescue like purple top and gammagrass. Many of these plants are natives and are better suited to our land conditions than the needier traditional forages. We still love tall fescue as it is uniquely adapted to our conditions and we have converted the better land to Novel Endophyte Tall Fescue.

In future editions I will expand on the concept of regenerative grazing and discuss specific things we do on our farm to continuously improve the ability of our soils to support a high level of forage production, and thereby more efficient production of beef. I don’t necessarily agree with all that is being said in popular circles about regenerative grazing and want to help our farmers better understand the principles behind continuous pasture improvement.

It is a very complex and interesting topic, and I look forward to exploring the details that have allowed us to stay competitive and to build a system that will continue to function far into the future without many of the expensive external inputs that in some cases can have a negative impact on the ecosystem.

~ Matt Poore, NC State and the Alliance for Grassland Renewal. A version of this article previously appeared in the Carolina Cattle Connection

The Alliance for Grassland Renewal is a national organization focused on enhancing the appropriate adoption of novel endophyte tall fescue technology through education, incentives, self-regulation and promotion. For more resources or to learn more about the Alliance for Grassland Renewal, go to www.grasslandrenewal.org